Nebulae and star clusters

Over time, the densest parts of the regions of dust in galaxies collapses into

smaller and smaller regions due to self-attraction by gravity, thereby getting

denser and denser. These are dark nebulae, visible only by the fact that they

completely block our view of anything beyond them, so they look like black spots

in the sky. In the center of these dark nebulae, very dense regions collapse

to form new stars. The largest of these new stars give up such intense light that

they blow away most of the nearby dust, and brightly light up the blown-away dust

so long as it remains somewhat nearby. Two such bright nebulae are visible with

the nakid eye, and look spectacular in telescopes.

M42

M42 is the great nebula in Orion. First an image from the Anglo-Australian telescope:

(Copied from: http://www.seds.org/messier/m/m042.html)

Notice how the deepest part of the blown-out cavity is hidden behind the near

edge of the cavity, but some regions of dust in that near edge are thin enough

that light from the inside is leaking through.

Here's an image by Robert Gendler showing just the central part of the nebula:

(Copied from: http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/ap020213.html)

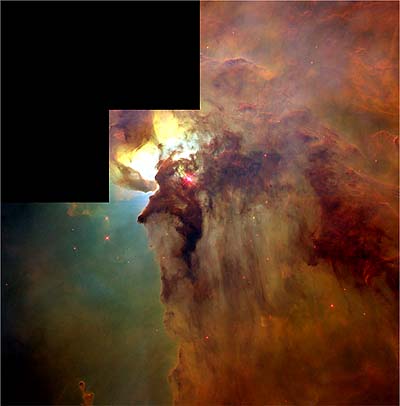

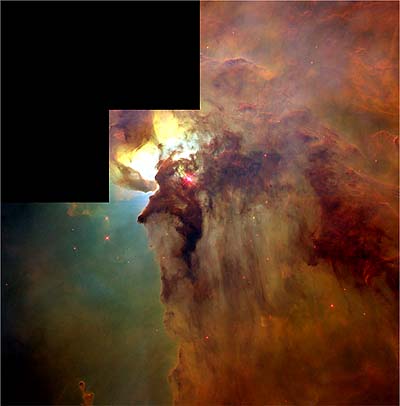

M8

M8 is the "Lagoon" nebula, located near Sagittarius. First an image from the

Anglo-Australian telescope:

(Copied from: http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/ap980707.html)

Next, an image by Barba, showing the central part in higher resolution:

(Copied from: http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/ap010820.html)

Notice that the cavity is facing us nearly directly, so the deepest part is

directly visible instead of hidden behind an edge of the cavity. Also notice

the small very dark spots where the dust is collapsing to form new stars

or small clusters of stars.

Finally, here's a very high resolution image of the centermost part of

the nebula, taken by the Hubble Space Telescope:

(Copied from: http://hubblesite.org/newscenter/newsdesk/archive/releases/1996/38/)

M44

After a very long time, nearly all the dust in a nebula has either formed stars or

been blown completely away, so all we see in that region are the long-lived stars

that remain. Here's an image of such a star cluster, M44, the "Beehive" cluster,

also known as "Praesepe", taken by Kopernik:

(Copied from: http://www.kopernik.org/images/archive/m44.htm)

Most of the bright stars in the central region are actually members of

the cluster, whereas most of the stars elsewhere in the image are unrelated

stars in the background, but it's difficult to be sure exactly which are which by

viewing such an image. We need to measure the actual distances to the individual

stars to be sure which stars are really in that region of space, hence probably

members of the cluster, and which are much closer or further away hence surely

unrelated.

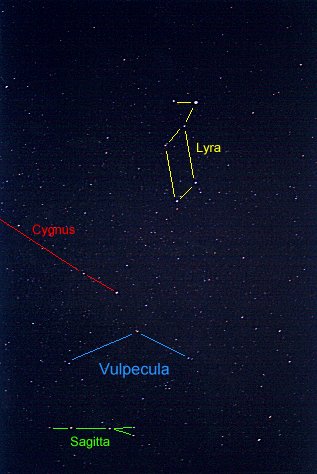

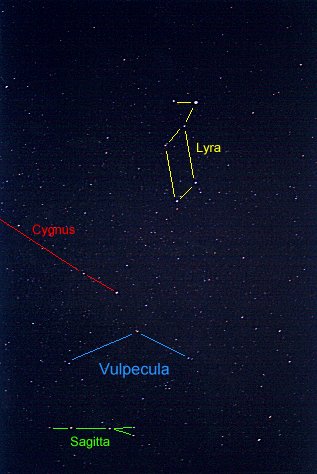

Col399

Here's a wide-angle image modified by adding lines to use as a star chart,

showing Vega in Lyra at the top, and the easy-to-recognize

(but hard to find unless you know where to look)

Sagetta (arrow shape) near the bottom.

With binoculers it's easy to sweep this region and see all the stars shown here.

If you sweep upward from the rightmost end of Sagetta, to the next semi-bright

star, then to the right and slightly up from there, you see a strange shape like

an upside wooden coathanger, with the stars of the hook brighter than the

stars of the wooden bar. Can you see it in this image?

Here's a wide-angle image modified by adding lines to use as a star chart,

showing Vega in Lyra at the top, and the easy-to-recognize

(but hard to find unless you know where to look)

Sagetta (arrow shape) near the bottom.

With binoculers it's easy to sweep this region and see all the stars shown here.

If you sweep upward from the rightmost end of Sagetta, to the next semi-bright

star, then to the right and slightly up from there, you see a strange shape like

an upside wooden coathanger, with the stars of the hook brighter than the

stars of the wooden bar. Can you see it in this image?

(Copied from: http://www.slivoski.com/astronomy/vulpecul.htm)

Here is some text to fill up all the left and flow below the image:

(In several recent Sky & Telescope issues there are pictures showing a wide

region of the sky, but at high resolution. In most of these images, it's possible

to see the coathanger right there in the image if you know where to look up-right

from Sagetta. Look below Cygnus to find Sagetta.)

(In several recent Sky & Telescope issues there are pictures showing a wide

region of the sky, but at high resolution. In most of these images, it's possible

to see the coathanger right there in the image if you know where to look up-right

from Sagetta. Look below Cygnus to find Sagetta.)

(In several recent Sky & Telescope issues there are pictures showing a wide

region of the sky, but at high resolution. In most of these images, it's possible

to see the coathanger right there in the image if you know where to look up-right

from Sagetta. Look below Cygnus to find Sagetta.)

(In several recent Sky & Telescope issues there are pictures showing a wide

region of the sky, but at high resolution. In most of these images, it's possible

to see the coathanger right there in the image if you know where to look up-right

from Sagetta. Look below Cygnus to find Sagetta.)

(In several recent Sky & Telescope issues there are pictures showing a wide

region of the sky, but at high resolution. In most of these images, it's possible

to see the coathanger right there in the image if you know where to look up-right

from Sagetta. Look below Cygnus to find Sagetta.)

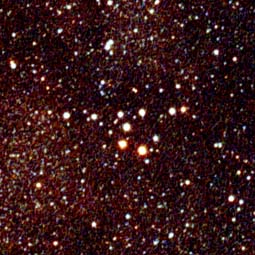

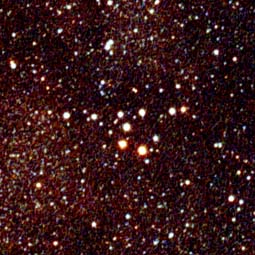

Here's an uncredited image showing a higher resolution view of just the coathanger

and nearby stars:

(Copied from: http://www.seds.org/messier/xtra/ngc/brocchi.html)

So what a strange looking star-cluster that seems to be! But alas,

it's not a real cluster. The Hipparcos satellite measured the distances to most

of the nearby stars, including the stars in the coathanger, and each is at a very

different distance from any other, so the stars aren't really near each other

at all. They are merely aligned, by chance, nearly along a line-of-sight from

Earth out into space, so they only look like they are related when viewed from Earth

or anywhere else along that particular line, but when viewed from any other

direction they'd be strewn across the sky so that nobody would even notice them.

This is a picture of me, but none of the earlier images are mine,

but the descriptive text is mine:

This is a picture of me, but none of the earlier images are mine,

but the descriptive text is mine:

Copyright 2004 by Robert Elton Maas

Link back to my home page

Here's a wide-angle image modified by adding lines to use as a star chart,

showing Vega in Lyra at the top, and the easy-to-recognize

(but hard to find unless you know where to look)

Sagetta (arrow shape) near the bottom.

With binoculers it's easy to sweep this region and see all the stars shown here.

If you sweep upward from the rightmost end of Sagetta, to the next semi-bright

star, then to the right and slightly up from there, you see a strange shape like

an upside wooden coathanger, with the stars of the hook brighter than the

stars of the wooden bar. Can you see it in this image?

Here's a wide-angle image modified by adding lines to use as a star chart,

showing Vega in Lyra at the top, and the easy-to-recognize

(but hard to find unless you know where to look)

Sagetta (arrow shape) near the bottom.

With binoculers it's easy to sweep this region and see all the stars shown here.

If you sweep upward from the rightmost end of Sagetta, to the next semi-bright

star, then to the right and slightly up from there, you see a strange shape like

an upside wooden coathanger, with the stars of the hook brighter than the

stars of the wooden bar. Can you see it in this image?

This is a picture of me, but none of the earlier images are mine,

but the descriptive text is mine:

This is a picture of me, but none of the earlier images are mine,

but the descriptive text is mine: