Is Tanking a

Viable Team Building Strategy?

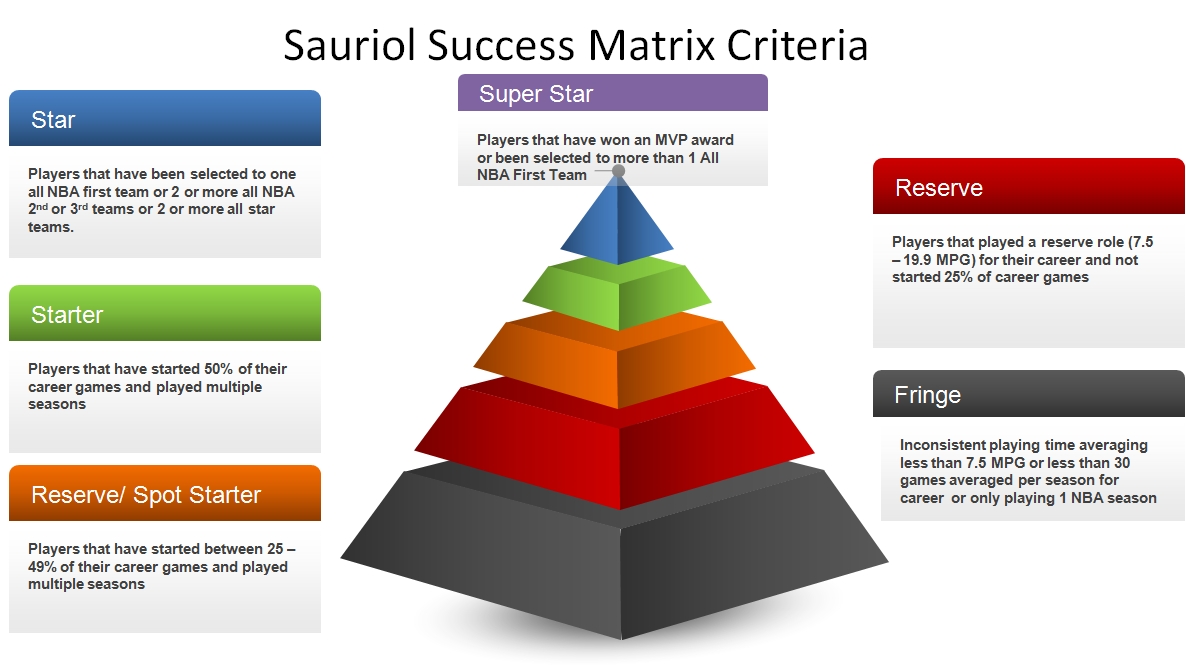

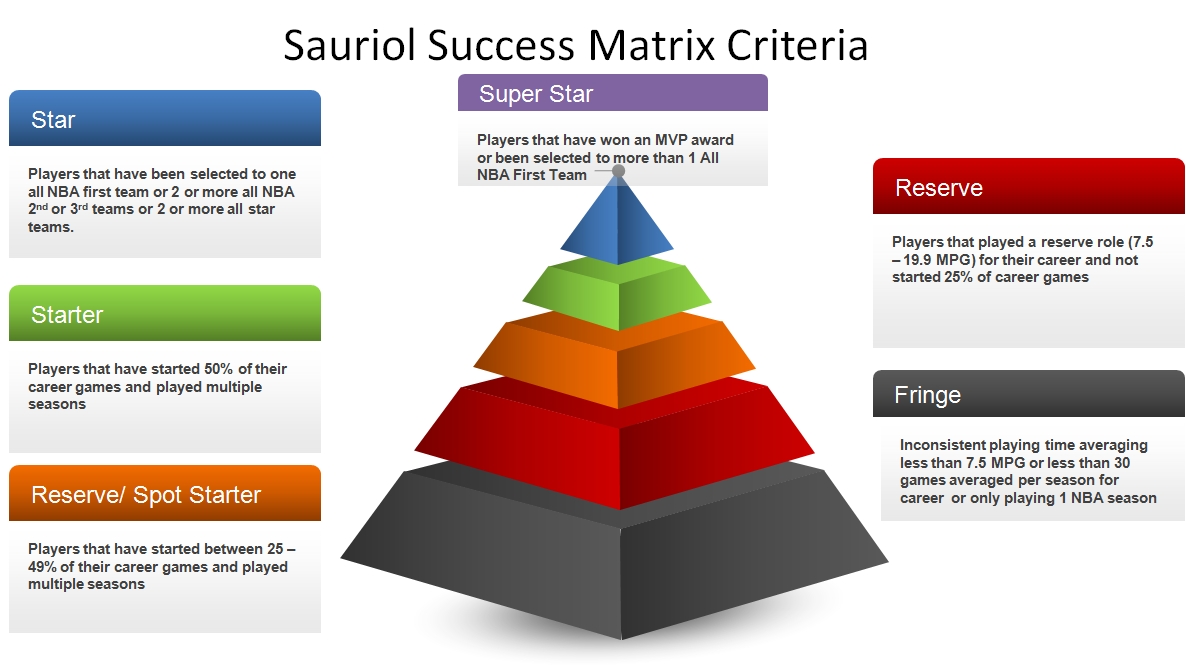

Introducing the Sauriol Success Matrix

By David Sauriol

Email the author

1 January, 2018

(Editor's Note: David Sauriol is a student that I had in a class that I teach at

SMWW.

During that class, I generally advise not to create a player-valuation system because

several exist and because improving upon them is very hard. What David is introducing here

is actually a simplified system that separates from an analysis of how players add to winning,

but creates a more analytics-independent classification system. This is useful

because it is easy and because a lot of people think this way. It can be used in concert

with more analytically-based metrics to look for where analytics and public perception are different.

It can be used in a lot of other ways, but I'll let David take it from here.)

Success

not just in basketball, but also in life is a highly subjective thing. What you personally see as success in a NBA player

might be a lot different than what I personally see. Is a player successful if

he can score 12 points a game or have 8 rebounds per game? Analysts and talent

evaluators could debate forever what the thresholds statistically would be, and

even still it would be very contextual. The Sauriol Success matrix (or SSM) was

created to provide a uniform framework for classifying the levels of success of

NBA player careers based on unambiguous but simple statistics.

The SSM uses the most direct sources to

determine what constitutes NBA career success: the views of NBA coaches, media and

executives. These are the people that will decide which players get into games,

start games, are selected to All-Star and All-NBA

Teams, and even how long their careers last. By analyzing the number of All NBA team appearances, All-Star

Game appearances, seasons played, games played, games started, and minutes

played, the players are grouped into six categories:

- Superstars,

- Starters,

- Reserve/Spot Starters,

- Reserves, and

- Fringe Players

The

first four tiers – Superstar, Star, Starter and Reserve/ Spot Starters –

cumulatively make up another grouping, “Core Rotation” which essentially indicates

players that play regularly. All relevant statistics required for the SSM have been available since 1981.

Tiers

of the SSM

The following graphics show the SSM tiers

and a simplified version of their basic rules. Though the rules have some

nuances to handle edge cases, these simplified rules capture a lot. The

detailed elements of the SSM and how to calculate it are found

here.

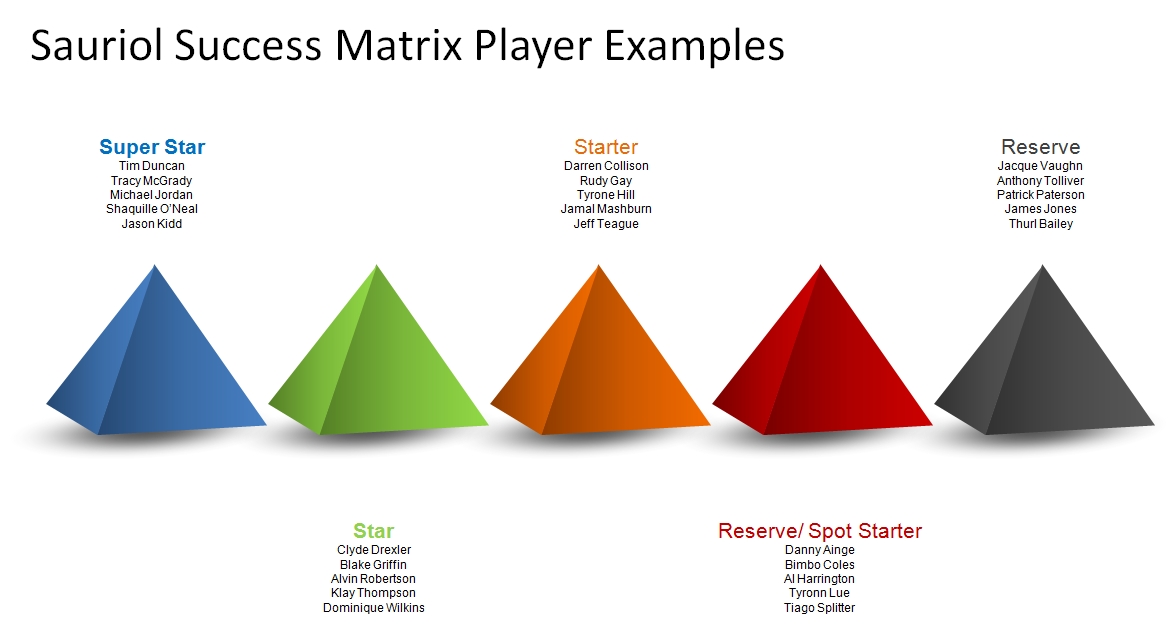

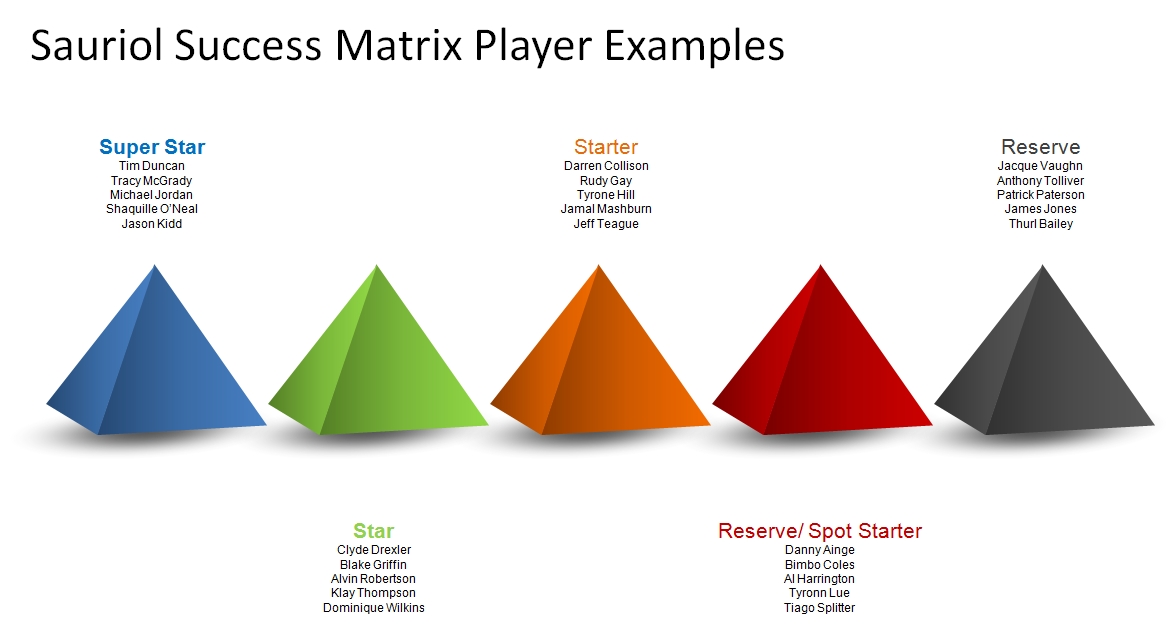

Look at the following graphic to see examples

of players since 1981 that fall into each tier of success.

Why

develop the SSM when a lot of player rating methods exist?

Whereas other rating systems rank players

numerically, the SSM is a categorical system that takes some basic statistics

and general consensus to classify players broadly into categories. This

distinction means that rather than viewing players individually they can be

studied as a group within their SSM classification. For instance, the 399

players classified as “Starters” can be examined with high quality analytics to

help understand who is “underrated” and “overrated” in a systematic way. The

SSM also simply provides a summary of a lot of the basic stats people start

with when discussing players – which is commonly used in making draft

decisions, trade decisions, or starting contract negotiations.

What

can the SSM Do?

By being a good historical reference

on players, the SSM can also play an important predictive

role in uncovering the next successful NBA players. Historical documentation of

the factors that have led to Superstar, Star, and Starter level players previously

can be combined with existing analytics (like for the Draft) and scouting methods to uncover players

with similar indicators of success. This means that by sorting through both

statistical (ex: a player’s career rebounding percentage) and non-statistical

(ex: where a players is from) factors, the SSM can help basketball talent

evaluators predict future successful players.

Of course this is not all it can do. The

following case study will show one of the SSM’s potential uses.

Is

Tanking Worth it?

Trust the Process… that’s what they have said around

Philadelphia, beginning with the period with Sam Hinkie as general manager.

The Stanford MBA grad cum NBA general manager felt that he was using the only

device at his disposal to acquire a Superstar - tanking three straight seasons!

In his view, a team needs a Superstar to have any chance of winning an NBA

title. Time is going to show whether Ben Simmons or Joel Embiid

becomes that Superstar he coveted. In the meantime, however, the SSM can be

used to look at the question historically to see if tanking gives a good chance

for a team to land a Superstar in a single season or, like the

Sixers, over multiple seasons. The Sam Hinkie

teams are a useful example, as from 2013 team to the 2016 team (not in

sequential order), these teams had the worst, second worst, and third worst

records in the NBA.

First, see the table below for some example #1 picks

that qualify as Superstars and Stars under the SSM method. Obviously, getting access to a pool of players that has

included Lebron James, Hakeem Olajuwon and Shaq “might”

be worth enduring some losing. I say “might” as it is hard to say culturally

what extended losing potentially does to a team.

On the other hand, Derrick Coleman and Ralph Sampson may have qualified as Stars due to

their All-Star selections and their teams may have been happy to have had them, but whether

they really added as many wins as true stars is up to analytics.

|

SSM Tier

|

Players

|

|

Superstars

|

Anthony Davis, Tim Duncan, Dwight

Howard, Allen Iverson, Lebron James, Hakeem

Olajuwon, Shaquille O’Neal, David Robinson, Derrick Rose

|

|

Stars

|

Mark Aguirre, Elton Brand, Derrick Coleman, Brad

Daugherty, Patrick Ewing, Blake Griffin, Kyrie Irving, Danny Manning, Yao

Ming, Glenn Robinson, Ralph Sampson, John Wall, Chris Webber, James Worthy

|

The History

of the Draft Lottery

Prior to 1985, the teams drafted in reverse

order of their record, with no random chance involved. This meant that teams truly could tank to get the first

pick. It took a while, but the NBA eventually realized that teams would go through the pain of

intentionally losing games to try to get players like Ralph Sampson and Hakeem

Olajuwon. So in 1985, they created the first draft lottery which gave all

non-playoff teams an equal chance of getting the 1st through 14th picks. Only 2

years later in 1987, this was changed to allow reverse order by record for all

but 3 teams. Originally, the odds were fairly low for the team with the worst

record getting the first pick sitting at 16.67%. These odds were altered in

1994 to 25% and again in 2005, with the latter changing the odds for picks

below first. The odds were changed again at the 2017 NBA board of governors

meeting. Coming into effect at the 2019 Draft lottery, the first 3 teams will

all have a 14% chance of receiving the first pick.

Lessons

from the 76ers

So what does this mean for the formerly Sam Hinkie

led 76ers? Let us consider the single season

finishes (worst record, second worst record, etc.) for those teams and look at

the odds historically that they, or any team that finished at the same

position, would have landed a Superstar or a Star to make their tanking worth

it. Shown below are the applicable draft lottery

odds (during the Hinkie years) that are then multiplied by the odds of landing a specific SSM tier player,

resulting in an overall probability of getting a Superstar, etc., based on record.

As you can see the odds of getting a Star level player are fairly flat from the

worst record to the sixth worst record, declining by about half from first worst to sixth worst.

The Superstar chances decline by more than that and drop under 1% at around the tenth pick.

|

SSM Category

|

Worst Record

|

2nd Worst Record

|

3rd Worst Record

|

4th Worst Record

|

5th Worst Record

|

6th Worst Record

|

NBA Player Overall

|

|

Superstar

|

12.35%

|

11.84%

|

11.31%

|

10.09%

|

7.40%

|

3.96%

|

1.21%

|

|

Star

|

22.36%

|

21.01%

|

19.52%

|

17.64%

|

15.43%

|

13.82%

|

4.02%

|

|

Star or Superstar

|

34.71%

|

32.85%

|

30.83%

|

27.73%

|

22.83%

|

17.78%

|

5.23%

|

Figure 1: The odds of the

Philadelphia 76ers landing top picks and their corresponding chance of A)

getting a Superstar and B) Either a Superstar or a Star level player based upon

that chance.

2013-14 The Sixers were 19 – 63

and finished 29th out of 30 teams in the league. In a normal year, as

you can see in Figure

1,

even with the second worst record it is no easy feat to land a Superstar level Player.

The odds of landing a Superstar player historically, not accounting for the

specifics of the 2014 draft class, are 12%. They improve to 21% for landing a star, or 32.85%

of landing one or the other.

In that year, the Sixers fell to the third pick (with the second worst record) but were

able to land the consensus top player in Joel Embiid

because of medical concerns. Time will tell if Embiid

will be able to hold up physically. He has already missed his entire first two

years in the NBA due to injury, but he has shown in very limited time in his third

and fourth years the talent that earned him the label “Olajuwon with a

jump shot”.

2014-15: The

Sixers were 18 – 64 and finished 28th out of 30 teams in the league (or third worst).

With this record, a team would have a 11% chance of

drafting a Superstar and a 20% of a Star for a combined 31% probability

of getting one or the other. In this draft, the Sixers got the third pick and

selected Jahlil Okafor. At this point in time, Okafor is a player who would have been better playing

10 years ago as he is struggling to find a place in the modern NBA. He did put

up solid numbers his first seasons but advanced analytics have consistently

shown that his team is better when he is not playing. In fact, in 2017, the Sixers did not pick

up his fourth year rookie option.

2015-16:

The Sixers were 10 – 72 and finished 30th out of 30 teams in the

league, the first year that the Sixers “succeeded” in tanking with the worst

record. Even with the worst record in the NBA, the Sixers only had a 12%

chance of getting a Superstar and 35% of getting either a Star or Superstar.

The Sixers did get the first pick in this draft and selected Ben Simmons. Like

Joel Embiid before him, he ended up missing his entire

rookie year due to injury. In his second year, there are some very encouraging

signs that he may develop into a Superstar or at least a Star level player. With

both these players, they are clearly Starters by the SSM method, but it will

take time to determine if they are Stars or better.

Overall, the 76ers were a bit lucky to have not fallen

further in the Lottery than they did. They were also lucky - in a sense - to have had Embiid's

injury issues show up pre-Draft and deter teams ahead of them from drafting him. (How different

would the league look had the Cavs taken Embiid over Andrew Wiggins, who they traded to get

Kevin Love?)

Final Thoughts on Tanking

Beyond the Sixers and looking at the

numbers for a single season, one has to question tanking as a team

building strategy. Trying to get "ahead" by losing even more than some of the other

bad teams doesn't dramatically increase the blind odds of getting a Star. Getting

a Superstar is easier in the worst five records, but those blind odds are still

roughly 1 in 10, not a guarantee. Not shown above are the pick-by-pick odds from #7 out to #14,

but the Star blind odds tend to be in the 10-15% range and the Superstar

values are in the 0.5% to 5% range. Whether teams find it valuable to

tank for those additional few percentage points is, in some ways, up to them, but

we put the probabilities out there for them to make calculations as they wish.

We call these odds "blind" because

they don't account for the quality of the talent in the Draft nor of the

quality of the scouts helping to select the player in the Draft. Any individual

team can improve the quality of their staff to make better picks probably as much as

through tanking, if not more. This then avoids the negative consequences of intentionally

losing, such as

·

Financial: The majority of owners would

not be willing to see the brand of their team take such a hit. Multiple years

losing with a clear pathway towards success will definitely impact the ability

a team has to sell tickets to games, draw television viewership and sell team

merchandise.

·

Fan Base: Consistent losing will push

away a lot of casual fans and see them move to other sports. Beyond the revenue

loss this entails the more serious issue is that it could take years of success

to attract their interest again.

·

Team Culture: Losing at that level can

become systemic within the team and create a culture whereas losing is accepted

as “normal.” A culture like this might not simply reset with potential star

level players like Embiid and Simmons finally taking

the court together, it could take years to redefine itself into a positive.

(See this

for some previous work on the matter)

In conclusion, although the odds of landing

a Superstar are not amazing at any finish record wise, teams can still land

solid Starters with top draft picks. Within the draft lottery 75% of players

end up in the core rotation, meaning they are players who at least start between

25 – 49% of their career games and play regular NBA minutes. Often they are

better than that. This might not sound like much, compared to our previous

conversation about landing Superstar and Star players, but having these

foundational players are crucial for teams. For some context the rate of core

rotation players falls to 40% from picks 16 to 30 and down to 20% in the second

round. Collecting solid rotational talent has been a strategy that the Boston

Celtics have used to rebuild their roster. Once they had collected enough solid

players they had pieces that could be used to acquire a Star level talent in

Kyrie Irving via trade and attract other Star level free agents like Gordon

Hayward.

The

Future of the SSM

Evaluating whether tanking is a good NBA

strategy is just the tip of the iceberg. Here are a couple topics to look for

in the coming weeks.

·

What regions of the world

produce the most successful NBA Players?

·

Grading NBA trades using the

SSM

·

What is the architecture of NBA

championship teams? What is the SSM composition of some of those teams? Is

there a pattern?

Larger topics will be assessed using the

SSM also. Two major projects I will be looking into are first evaluating

college or international performance to look for indicators in young players

that can be used as predictors for future NBA success. Secondly, I am looking

at NBA players first three seasons to identify traditional and advanced

statistical indicators that can also be later used as predictors of success for

the remainder of that player’s career.